An International Education

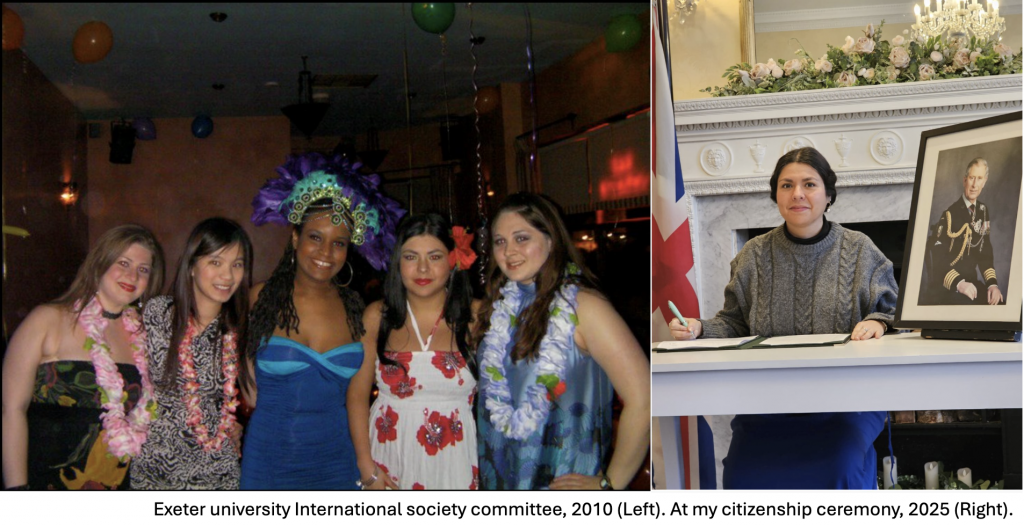

A few days ago, I became a British citizen; while standing in a room full of other immigrants pledging our allegiance to the British crown, I thought about the journey it has taken to get here. Fifteen years ago, I came to this country as a young student. My first experience with the UK was not a British one but a rich multicultural slap in the face. I had never been amongst such a diverse group of people, and this was one of the most enriching experiences of my education.

In my experience both as a student and now as an educator this exchange has not only been key in my practice as an artist, but also, it has shaped my world views. The influence of others’ cultural experiences has deepened my knowledge and influenced my teaching. In my years at university, through conversations outside the classroom, I entered some of the most fascinating intellectual discussions that challenged me and gave me a wide variety of perspectives. Listening and sharing what it is like to grow up in different parts of the world, I believe gives us a unique perspective, a human-centered one that allows for empathy.

History shows us these exchanges have had a massive impact on shaping political views. During the 20s and 30s, hundreds of representatives of national liberation countries attended communist universities (Filatova, 1999). Between the 60s and 80s communist countries offered thousands of scholarships to students from Africa, Latin America, South Asia, and the Middle East(Central Intelligence Agency, office of global issues, 1989). These institutions had an enormous influence on the history of the 20th century.

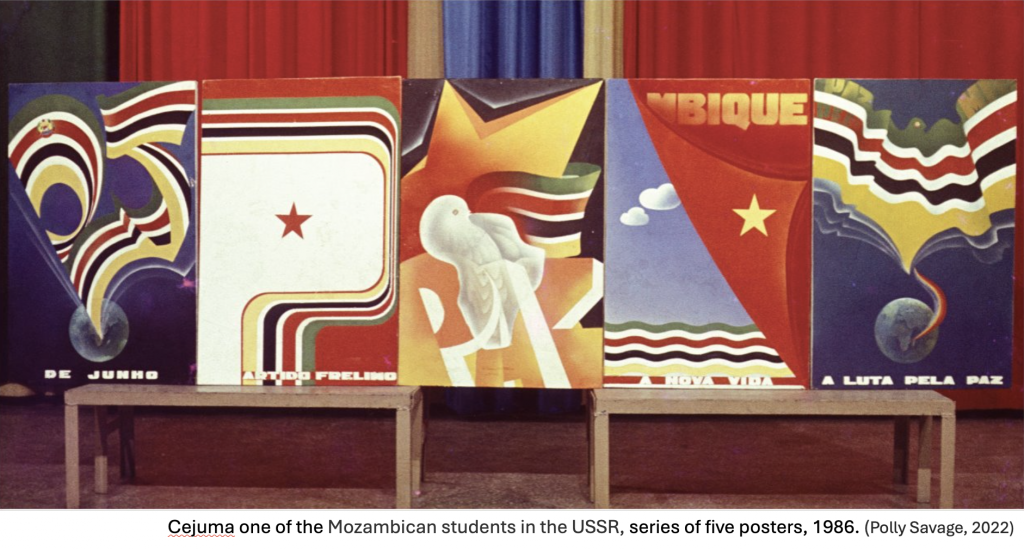

To give a more specific example in 1981 a group of Mozambican students traveled to the USSR to study art and design. Their experience is fascinating, they had to learn Russian and were forced to engage with a very limited curriculum only focused on Russian artists and practices. However, despite the limitations, these students managed to form a critical approach to their learning and developed their own aesthetic practice. These students were able to break free from the boundaries they were given, in part through the sole exercise of learning new skills but in greater part through the cultural interchange they were having with other students. This community offered International students a place of solidarity. In addition, it created networks of artists and aesthetic exchanges that would prevail and reshape political ideals (Savage, 2022).

Now more than ever we must investigate the influence international exchange has. Learn from the past and question, as educational institutions and teachers how are we influencing students? How can we ensure that as educators we create spaces where students can explore their differences? And how can we question the institutions we work for so that international students are seen as intellectual assets instead of financial ones. How will increased fees impact the perspectives of students, if only privileged students can access education? In a world where divisions seem to be more prevalent, the nurturing of diversity in education is key to fostering tolerance.

References

Central Intelligence Agency, office of global issues (1989). Moscows third world educational programs: An investment in political influence, The Princenton Collection. chromeextension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/DOC_0000500645.pdf (Accessed : 08/01/2025).

Filatova, I. (1999). Indoctrination or Scholarship? Education of Africans at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East in the Soviet Union, 1923‐1937. Paedagogica Historica, 35(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/0030923990350104 (Accessed : 08/01/2025).

Polly Savage, ‘The New Life’: Mozambican Art Students in the USSR, and the Aesthetic Epistemologies of Anti-Colonial Solidarity, Art History, Volume 45, Issue 5, November 2022, Pages 1078–1100.

Decolonizing our teaching practice

My mother is a historian, so I’ve grown up with a constant reminder of the past. Growing up in a country, Mexico, where Western influence is increasingly taking over, she has never let me forget my roots and our complicated colonial past.

When I came to the UK, I realized my knowledge was very different from the knowledge of my European peers, while I was expected to know Europe’s history, they were not expected to know mine. This extended to other subjects, where sometimes I felt my understanding of the world was seen as mystical or unconventional.

Now working at a university, the idea of decolonization really resonates with me. But what does it mean to decolonize and how can we do it in a way where it has a real impact rather than just being a box we can tick (Tate and Bagguley, 2017).

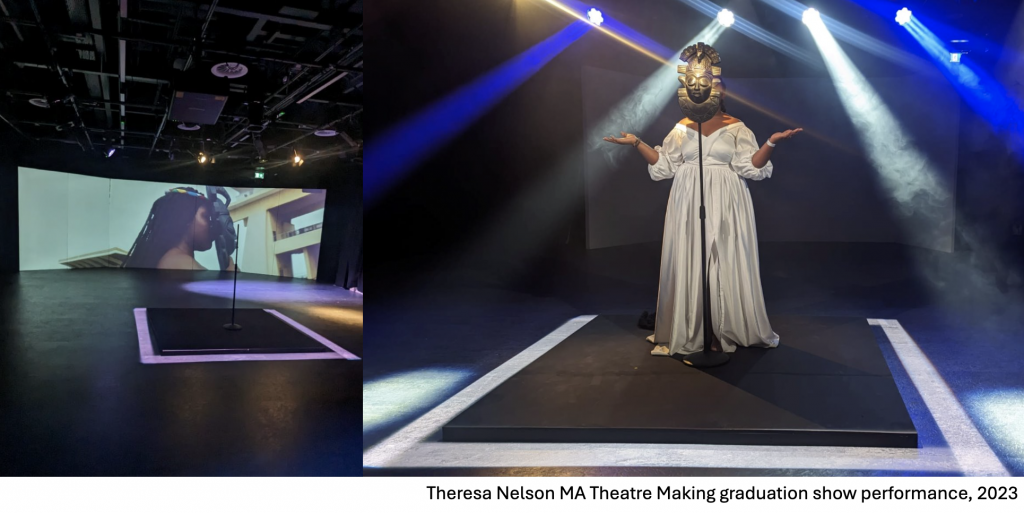

I like the idea of decolonizing our minds, as teachers it is important to not only recognize the different perspectives of our students but allow these perspectives to challenge our own. Last year, for example, we supported a student in the development of a show about African objects stolen by the British Museum (Top image). I also learned how to play Mahjong a traditional Chinese board game which was the vehicle a student used in her storytelling (Image below). It’s a privilege to be able to learn and help students explore and celebrate different cultural perspectives.

The idea of Columbian philosopher Santiago Castro Gomez ‘The hubris of the zero point’ proposes that when there is a detached point of observation the knowing subject ends up interpreting and classifying others establishing intellectual and racial hierarchies (Mignolo, 2009, p.1). As people with individual experiences of the world, being neutral is not realistic, having a form of bias is inescapable, so using the opposite of the above could be a helpful exercise when dealing with ideas we don’t agree with or understand. Starting from a compassionate point of observation that invites us to actively fight against our assumptions.

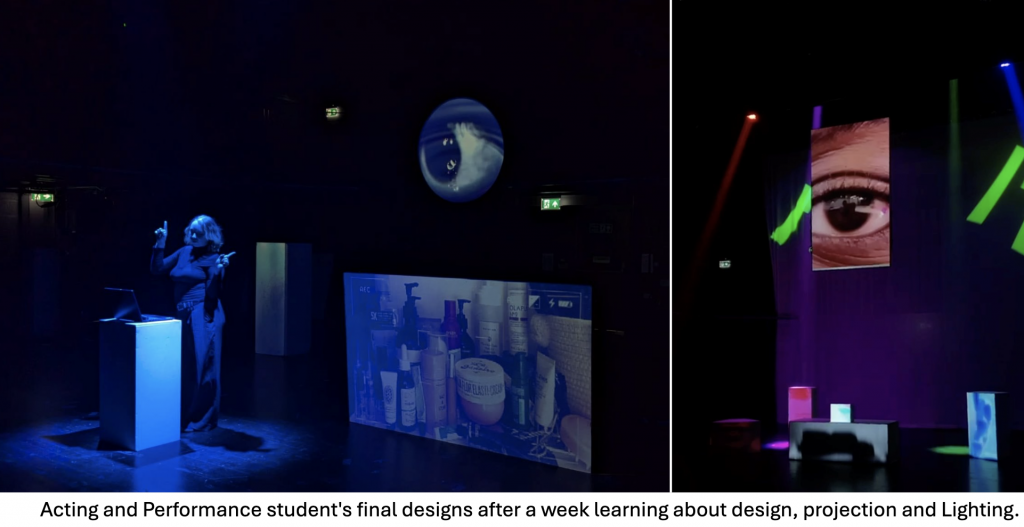

We have an important role to play in the efforts to decolonize knowledge, it is not just about making sure we produce, consume, and impart knowledge that includes all narratives. It is also about approaching our teaching practices with openness and empathy (Crilly, 2019). Allowing ourselves to be wrong and to be questioned. Asking ourselves: how have the effects of colonialization, socialized us? How has this affected our beliefs not just in terms of our intellectual knowledge, but in how we view relationships, food, work, money, leisure, and even our understanding of time and space itself. For example, when I facilitate students in designing collaboratively for their performances in our theatre. I challenge them to discuss how the topic is approached in their different cultures and how they can incorporate day-to-day aspects of their personal experiences and relate them to the topic they are exploring. Questioning where these beliefs come from can lead to a more person-centered way of teaching and learning where we see students as our equals and can have a better understanding and appreciation of their ideas.

References

Crilly, Jess. (2019) “Decolonising the library: A theoretical exploration.” Spark: UAL Creative Teaching and Learning Journal 4.1 (2019): 6-15.

Mignolo, W.D. (2009) ‘Epistemic disobedience, independent thought and de-colonial freedom’, Theory Culture and Society, 26(7/8), pp.1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0263276409349275 (Accessed : 15/01/2025).

Tate, S.A. and Bagguley, P. (2017) ‘Building the anti-racist university: next steps’, Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(3), pp.289–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2016.1260227 (Accessed : 15/01/2025).

“Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself.” John Dewey (1859-1952)

John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer. He was a major voice of progressive education and liberalism.

This week we spoke about the aims of education, and it really made me reflect about why I teach and how my background and experiences have shaped who I am as a teacher. Both my parents are teachers, I grew up coloring books or doing puzzles while my mother gave lectures. I vividly remember telling my mother I was never going to be a teacher and I never consciously intended to become one, life just happened, and teaching became something I greatly enjoy.

Even though my mom was an academic she always said you don’t need to go to university to be educated and this has always stayed with me. She instilled in me a love for learning beyond the classroom and I’m deeply grateful for that.

Perhaps this is why the Jhon Dewey quote really spoke to me. He believed education should prepare students for life itself and serve society as a force for innovation and reform (Dewey, 1966). I would add that our experiences outside of school also deeply inform our knowledge and behavior and should be integrated into how we learn and teach, showing sensitivity to the unique differences and needs of students (Hassen, 2023).

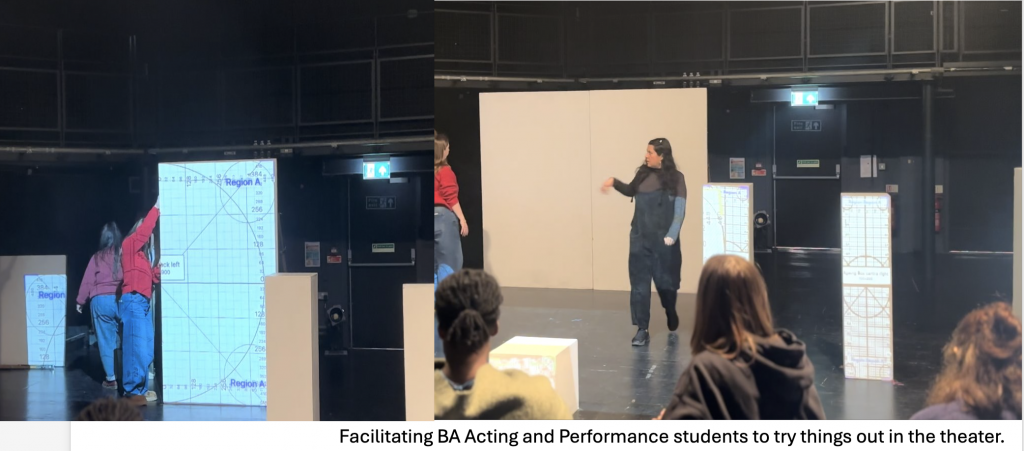

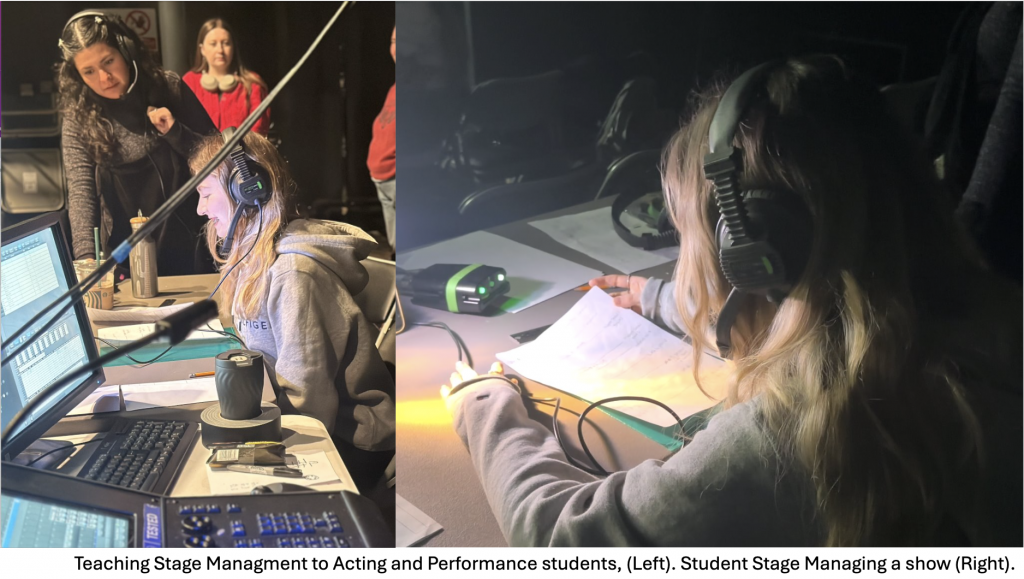

Dewey also championed learning by doing, a practice I strongly believe in especially when it comes to art and creativity. I can attest to students learning better when they are actively engaged because they are immersed in the present, moreover, it provides an opportunity to make mistakes and learn from them. For example, when helping students produce their performances, I encourage them to stage manage their productions themselves instead of doing it for them. This, apart from giving them new skills, makes something click in their minds, and they start understanding the links between all the different areas of the theatre.

As a technician in the theatre, I believe it is my role to let the students use the space as a playground where they become active recipients of knowledge. Where they can ask questions and where we can arrive at solutions together by trying things out, and testing what works and what doesn’t. (I expand more on how we provide opportunities for this in case studies one and two).

I teach because I like learning, I especially like learning from others. Education, as my mother taught me, is in everything, we should value our knowledge because it is unique to us, and value others’ knowledge for this same reason. People are vessels of vast and strange expertise and skills and celebrating this diversity of thought is something to be encouraged in higher education.

References

Dewey, J. (1966). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. The Free Press.

Hassen, M. Z. (2023). A critical assessment of John Dewey’s philosophy of Education. International Journal of Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijp.20231102.13 (Accessed : 12/02/2025).

Teaching the Hidden Curriculum

When I did my MA in illustration, I found myself really lost in terms of what was expected of me, I had done a previous degree in Molecular Biology where the aims and expectations of my learning were very quantifiable and therefore more straightforward. But in the arts having measurable outcomes seems problematic as it is hard to write up learning outcomes that measure imagination, risk-taking, creative problem-solving solving and intuition which are essential skills in the process of creativity and making art (Addison, 2014).

I find myself now on the other side, teaching art and design students, and I can see more clearly the challenges of finding ways to measure their learning. As a technician, my approach to teaching is very different from that of the academic body. Primarily because I don’t have to grade, the relationship I build with students is different, it is a relationship based on need, where students become active participants in their learning. It is a person-centered approach, that allows me to be more flexible and inclusive with my teaching. However, it is problematic as it relies on the students being the drivers. I worry many don’t get to learn the skills we have to offer simply because they don’t know how to engage as it is not a formal part of their units.

I find the lack of involvement of technical staff in the academic curriculum problematic. I see students who come to us with a huge lack of practical skills. This might be because assessment has a significant impact on learning (Davies, 2012). And often effort and engagement, which are the parts of the process where technical areas are involved, are not reflected in the grading. We risk students looking to tick off learning outcomes in their assessments rather than being present and collaborating with a project. If technicians were part of the design of a program there would be clearer ways to fit practical skills in the curriculum and more accountability for us and the students.

Moreover, the skills we teach in technical departments are often skills employers look for in students after they leave university. When I did my MA, I engaged fully with the technical departments and spent most of my time making and learning from technicians. I ended up leaving university and was able to find a job immediately because I had all these practical skills under my belt. So, I would like to see technical skills being incorporated in the Learning outcomes of the courses.

I incorporate learning outcomes in my teaching but use them more as a tool that gives a general structure, one that allows flexibility and personalized teaching. I don’t think we should rely on them as the only form of assessment as quality in art and design can’t be measured. Instead, we must encourage students to have a critical approach and engage in making and collaboration. Learning outcomes can serve as boundaries for students to formulate and find their own quarries so we can then support and facilitate the development of their ideas (Davies, 2012).

References

Addison, N. (2014) ‘Doubting Learning Outcomes in Higher Education Contexts: from Performativity towards Emergence and Negotiation,’ International Journal of Art & Design Education, 33(3), pp. 313–325.

Davies, 2012, Learning outcomes and assessment criteria in art and design. What’s the recurring problem? brightONLINE student literary journal, Issue 18, pp 1-7