Case Study 1: Knowing and responding to your students’ diverse needs

Contextual Background

As part of my teaching, I must guide students in the production process involved in live performance. I do this across different courses so the diversity in knowledge and skill is very wide. Moreover, I have to take into account the language barriers students may face and cultural and learning differences as our student body is very diverse.

Evaluation

I use a number of different strategies and resources to aid understanding.

The first step is to have an initial production meeting, I meet the students face to face, so they can explain their ideas in their own words. I start a document with them where we record everything.

Depending on their skill level I ask them for drawings, alternatively, we map out the stage they Invision together, using simple shapes and labeling everything.

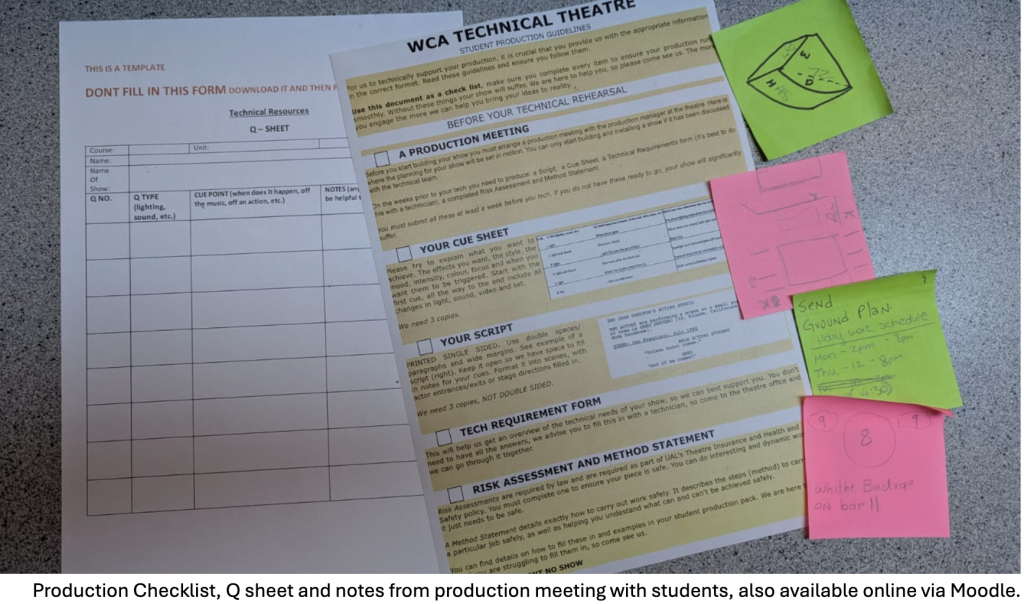

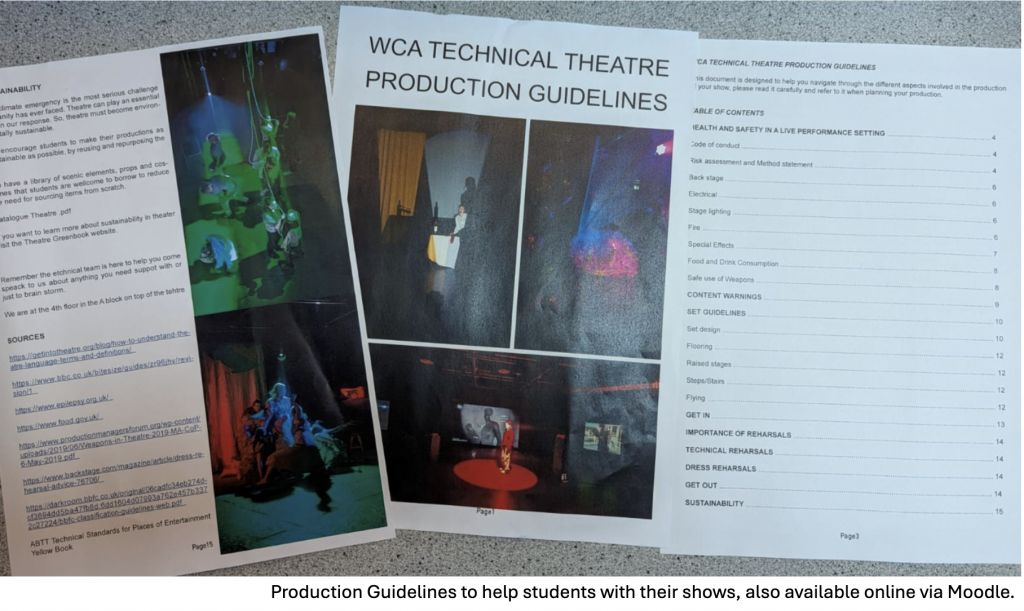

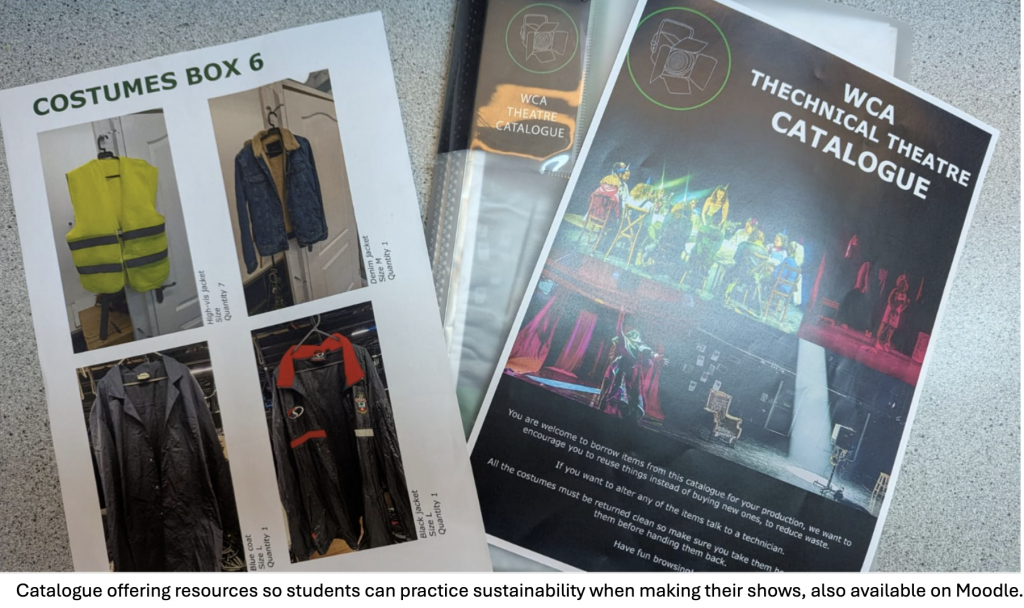

I give them a production schedule with clear deadlines. As well as a link to a database that has resources like our catalogue and guidelines to help them navigate the different steps.

Moving Forwards

I have developed a checklist (top image) I give to students; this has a very simplified list of the different steps they need to go through. I use dyslexia-friendly fonts, structure, and color, the document is an A4 piece of paper they can take with them so they can physically check the steps as they complete them, British Dyslexia Association (no date). Each step has a link to more detailed resources they can choose to engage with.

I would like to incorporate VARK modalities; by developing this resource so it can translate to an audio and a video format they can access through Moodle (VARK Learn Limited, 2024)

Being able to meet with students is an incredibly valuable strategy. As it gives them autonomy over their projects and encourages them to become active participants in the process. It is through listening to the students and giving them the space and patience to explain their thoughts that I can help them come up with creative solutions, and signpost them to the correct people. For example, if a student needs to build a platform where actors will perform. I either encourage them to use our resources, showing them a visual catalog or I get them to book a conversation with our scenic specialist and the 3D lab so together they can design and build a safe structure that directly responds to the student vision. I recognize, however, that for some students it may be challenging to have these meetings so there needs to be alternative ways of establishing a dialog with them.

In my experience giving them clear deadlines and scheduling regular meetings really impacts how they engage with the project, it also allows them to ask questions as the project develops. Recording everything in a live document that is clear and color-coded is also very effective as we can develop it together and it’s a place where all the information, they need lives.

Getting the students engaged is my main challenge, I would like to offer more opportunities to meet online and expand the formats of our current resources, so students have different options for engaging with the information as well as offering different ways of communicating with me.

References

British Dyslexia Association (no date) Dyslexia friendly style guide – British Dyslexia Association. https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/advice/employers/creating-a-dyslexia-friendly-workplace/dyslexia-friendly-style-guide#:~:text=Readable%20fonts,may%20request%20a%20larger%20font (Accessed : 22/01/2025).

VARK Learn Limited (2024) The VARK Modalities: Visual, Aural, Read/write & Kinesthetic. https://vark-learn.com/introduction-to-vark/the-vark-modalities/ (Accessed : 22/01/2025).

Case Study 2: Planning and teaching for effective learning

Contextual Background

As a theatre technician, one of the aims of education that speaks to me is equipping students with skills that will help them get employed. In most cases when students engage with us, it is the first time they encounter a working theatre, so we aim to give them opportunities to engage practically with the resources.

Evaluation

The theatre industry is a very broad one, so teaching students an array of technical skills is an effective way of ensuring they have more avenues for entering the world of life performance.

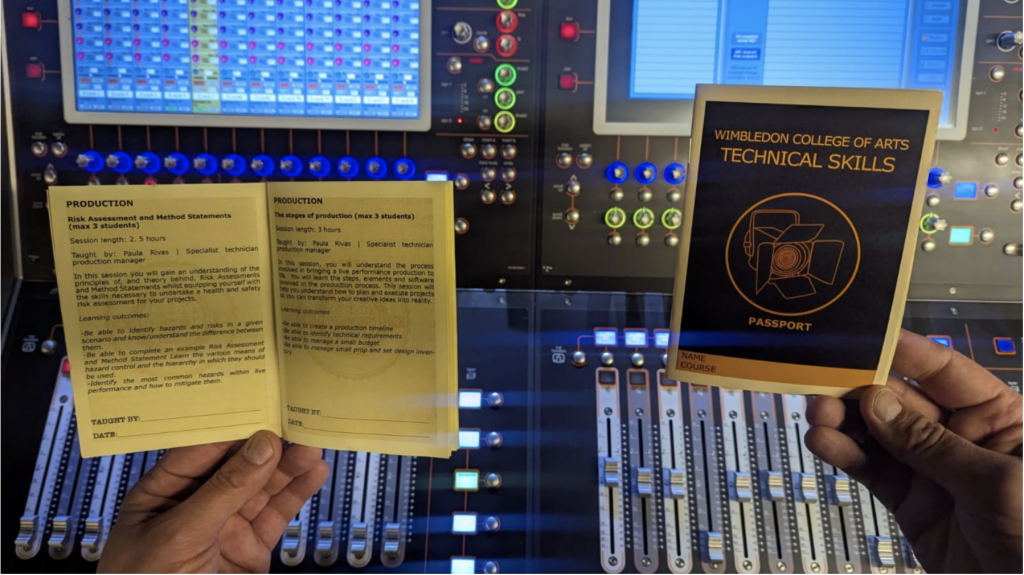

The team and I have implemented a technical skills passport as an effort to teach students skills outside their academic curriculum. More details of this are in my blog post Teaching the Hidden Curriculum.

Students can choose to engage with and pick and choose the technical skills that interest them. We offer a wide variety of options from production and stage management, which are my specialist areas to sessions in sound, lighting, rigging, and video. The sessions are taught in small groups or one-to-one. This is an opportunity for students to learn valuable practical skills. However, because it is not embedded in the curriculum not many students engage with it.

Moving forwards

Writing the skills passport was a very effective way of organizing the different skills we offer in the theatre. It allowed me to put into words the knowledge and practical skills I can impart to students. It also forced me to structure the different sessions and have clear session plans with learning outcomes. So, I will be applying this process more in other areas of my teaching practice.

The skills are taught based on needs and interests which means the students that engage with the passport come already with a framework of mind of wanting to learn. One of our challenges is how do we peack the interest of more students.

I try to keep a flexible framework since we support students from different courses and with mixed backgrounds and abilities, so I aim to tailor the sessions to their specific needs, for example, if the students are from a costume course I focus on how the costume is integrated within the technical areas of the theater.

The passport is a physical booklet we give to the students; every time they complete a skill within the booklet we stamp the corresponding page. We have found this is an effective way of engaging students to book more sessions, so we would like to implement more playful ways of engagement, such as offering a badge when you complete x number of sessions.

This is a relatively new resource so the outcomes from this year will be useful feedback for improving the resource and implementing new strategies. I have identified that my sessions need to be a little bit longer to cover all the content and I would like to have follow-up sessions where the students apply the skills to a specific project they are working on. I also have identified the need for an alternative space to teach the sessions, as the theatre is not always free to use for this purpose. In the same vein, I would like the sessions to be more formalized so that there is a time every week we can dedicate to teaching and developing the sessions. Moreover, I would like this resource to be more embedded in the academic units, so more students have an opportunity to engage with it.

Case Study 3: Assessing learning and exchanging feedback

Contextual Background

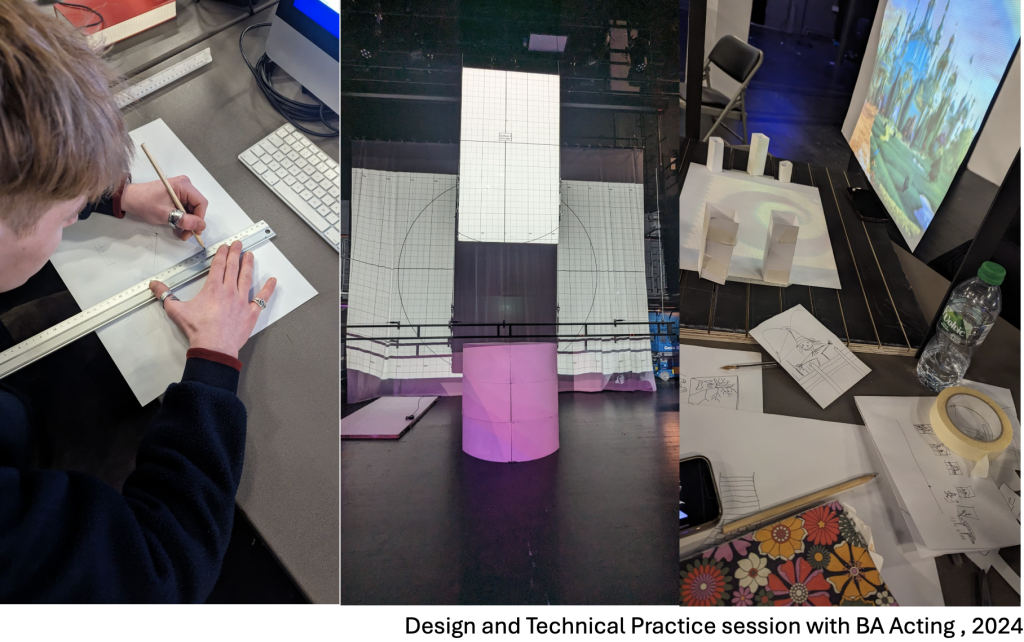

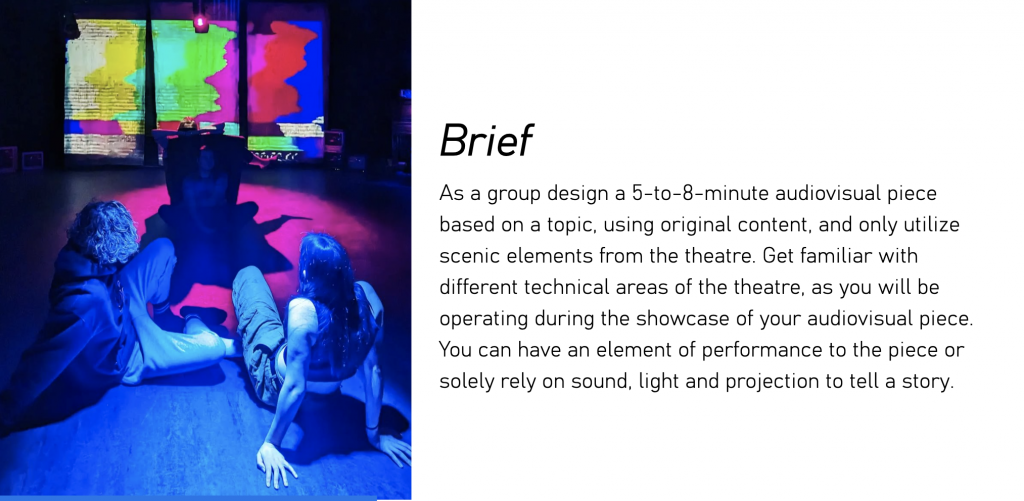

I teach the BA acting and performance third-year students a project aimed at giving them an understanding of how to transform a concept into an audiovisual performance piece, by engaging them in the different technical areas of the theatre. The project is assessed authentically (Wiggins 1989,1993). As it asks students to demonstrate their knowledge on specific tasks in a ‘real-world’ context.

Evaluation

The reason for this project is to equip students with authentic experience of working in a theatre, so they can have more autonomy and feel empowered with technical knowledge that they can integrate in the development of future projects.

There is no formal assessment of the work, and the project rather relies on collaboration and participation which if it’s done effectively results in a visually engaging performance, they can use in their portfolios. Moreover, it challenges students to collaborate effectively as the final product (the performance) is built upon all members of the group contributing to the tasks.

Moving forwards

We have received good feedback about the project from students, reinforcing the idea that in creative subjects learning by doing is key for student understanding (John Biggs, 2003). However, there is a desire by students to have more time for the project so they can engage more in-depth with the different elements involved and create a more complicated piece at the end.

The project is thought by me, alongside two other specialist technicians, who focus more on lighting and sound. The feedback from them has also been that it is challenging to teach such complex processes in such a short amount of time, so they are often only covering the basics.

We have also identified that group sizes need to be much smaller, 5 students maximum, to be able to give every student in the different groups a ‘specialized job’ so that their engagement is reflected in the final product. However, our main challenge is that we are only given a week to do the project with large cohorts, so we are forced to split them into groups of up to 10 as otherwise we wouldn’t be able to have time to go through all the different sessions needed.

The other challenge with having bigger groups is that some voices get overlooked and students with the stronger voice can be overpowering. As Ferguson, Hanreddy and Draxton (2011) state, “Giving students a ‘voice’ for active participation in decision-making about their learning environment has great potential for increased engagement. So, it is important we facilitate this. I do my best to encourage the quieter students to participate but I am on my own for the first part of the project, when all of the ideas and decision-making takes place, so monitoring this can be difficult. I would like to have some support in the teaching, so they can help me ensure everyone has a chance to speak.

Finally, I would like to develop the project so it can be incorporated into more units starting from year one so that students can progress in their learning and so that we can evaluate better such progress and thus we can tailor our support to individuals better. As well as giving students more opportunities to participate in real-life tasks that require them to produce tangible evidence of their learning (Herrington & Herrington, 2006).

References

- Biggs, J. (2003) Aligning teaching for constructing learning. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/aligning-teaching-constructing-learning (Accessed 12/03/2025).

- Ferguson, D.L., Hanreddy, A. and Draxton, S. (2011) ‘Giving students voice as a strategy for improving teacher practice,’ London Review of Education, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/14748460.2011.550435 (Accessed 12/03/2025).

- Herrington, J., & Herrington, A. (1998). Authentic Assessment and Multimedia: how university students respond to a model of authentic assessment. Higher Education Research & Development, 17(3), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436980170304 (Accessed 12/03/2025).