The Window Box, Written and directed by Megan Holman, BA (Hons) Contemporary Theatre and Performance.

Introduction

As a technician working closely with students on theatre productions at Wimbledon College of Arts (WCA), I am positioned in a unique space part practitioner, part facilitator, and part support system. My role gives me direct access to students’ creative processes, particularly during the production of their performances. This proximity has highlighted how much space there is to encourage more inclusive approaches, both in how students think about their work and how they present it to an audience.

I believe as artists and facilitators we have a platform and opportunity to use our practice to question, disrupt the status quo, and make audiences reflect on certain topics that matter to us. Moreover, we have a chance to give visibility to themes and people that tend to be overlooked.

This essay reflects on the development of a pilot workshop designed to support students in embedding inclusivity into their creative practices. It draws on my own experience, theoretical frameworks, and feedback from students and peers, while also exploring what I’ve learned about myself and my practice in the process.

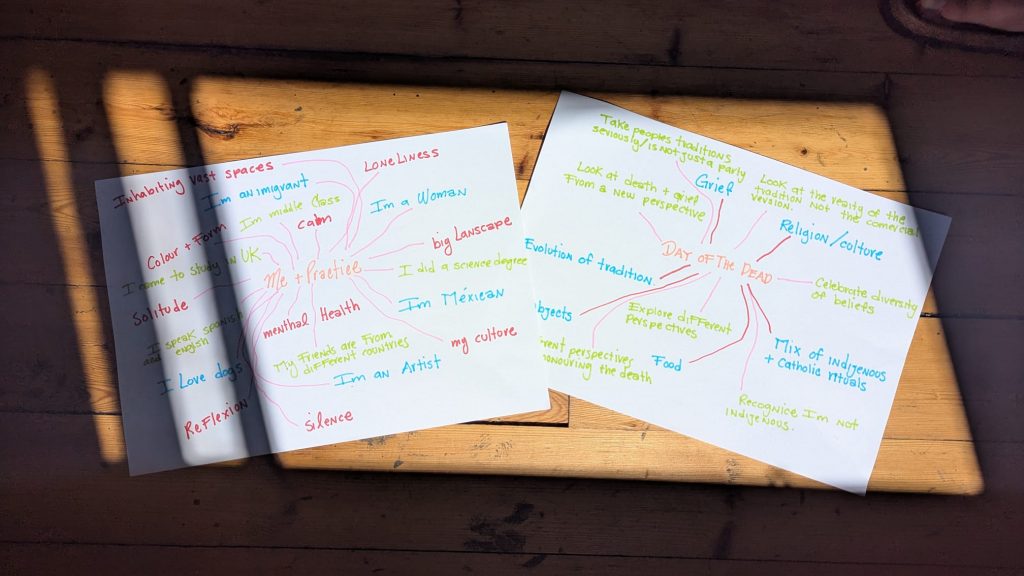

Reflecting on my own positionality was essential in designing this workshop. I am a Mexican woman and an artist with a background in both painting and community work. English is not my first language, and I have worked extensively in settings that include older adults, immigrants, and individuals with mental health support needs. These experiences have shaped how I see the world and understand inclusion not as a theoretical concept but as something deeply personal and rooted in lived experience.

Haraway’s (1988) idea of “situated knowledges” helped me frame my positionality not as a limitation but as a strength. My perspective is partial, yes, but it is also informed by a specific set of cultural, linguistic, and experiential intersections. Bringing this into the workshop helped foster a space where students felt encouraged to reflect on their own positions without fear of getting it wrong. I was careful to acknowledge that the session might raise difficult feelings and encouraged everyone to engage with empathy, not judgment.

Beyond the Cake, By Wei Shuai, BA (Hons) Contemporary Theatre and Performance.

Context and framework

As Production Manager at Wimbledon College of Arts, I have become increasingly aware of the limited inclusive practices within our theatre spaces. I work closely with students from a wide variety of cultural, economic, and linguistic backgrounds, and I’ve seen first-hand how structural and attitudinal barriers can impact their sense of belonging and creative agency within institutional theatre spaces.

The workshop was trialed with second-year students from the BA Contemporary Theatre Performance course at WCA. These students are in the early stages of shaping Unit 9 project, which invites them to create original work. It felt like the ideal moment to intervene so they can integrate inclusive practices into the design process rather than it being a one-off session that might not lead to practical change.

The workshop was divided into two main sections, each built around key concepts: intersectionality, positionality, and the social model of disability. These frameworks were chosen because they support a reflective, systemic analysis of identity and power.

Crenshaw’s (1989) concept of intersectionality was central in highlighting how various forms of discrimination (based on race, gender, class, disability, etc.) intersect to create unique experiences of privilege and exclusion. Positionality, as explored in feminist and decolonial theory (Haraway, 1988), encouraged participants to reflect on how their own identities and experiences inform their creative practice.

In the first half of the workshop, participants mapped their identity and practice visually. This reflective task enabled them to consider how personal experiences inform artistic decisions. They analysed their current project and explored what themes, values, and histories underpinned them. These exercises helped bring to the surface connections between the self and the work highlighting how identity is not external to practice but embedded within it.

We also spoke about the potential of inclusive theatre to create community and offer alternative ways of being and knowing inspired form Kuppers (2014) and Jaskolski (2021). These texts reminded me that inclusion is not just about accessibility but also about creative richness about allowing different voices, aesthetics, and ways of experiencing the world to shape the work from the beginning, not just at the point of presentation.

Participants were asked to reflect on moments of discomfort in engaging with art, drawing on Cox’s (2020) idea of discomfort pedagogy, which views discomfort as a potential catalyst for learning, especially within decolonial teaching. We discussed the power of art to challenge perceptions and how inclusive practice is not about avoiding discomfort, but using it constructively.

The second half of the workshop shifted focus from internal reflection to external impact. participants identified their intended audiences and considered the barriers those audiences might face when engaging with their work. We discussed inclusion as defined by Merriam-Webster (2024), as “the act or practice of including and accommodating people who have historically been excluded.” We also introduced the social model of disability (Oliver, 2004), which reframes disability as a result of environmental and structural barriers rather than individual impairments.

It was interesting to look at this within the context of theatre production, where access is often understood in narrow terms such as the addition of ramps, captioning, or other technical interventions. While these are important, the social model invites us to think more expansively: how might the norms, expectations, and creative decisions within a production inherently exclude certain individuals from fully participating as artists, audiences, or collaborators?

Death of a Party, Written and directed by Sascha Putri,BA (Hons) Contemporary Theatre and Performance.

Feedback and Evaluation

The workshop confirmed the power of reflection as a form of activism. Students welcomed the opportunity to bring their whole selves into the room and explore the ethical dimensions of their work. Some said it was the first time they’d been asked to consider inclusion as part of their creative process, not just an institutional tick-box.

Their reflections extended beyond physical access to include emotional, linguistic, and cultural considerations like the use of academic language, the importance of content warnings, or the erasure of minority narratives. This was deeply moving and reflected a shift in how students began to imagine access not as limitation, but as creative opportunity and shared responsibility.

Presenting the workshop to peers also generated useful feedback. One particularly resonant point was about hierarchy in theatre spaces how technical and production teams are often undervalued. This struck a chord. Over the years, with growing production demands, technicians have increasingly been servicing students rather than enabling them. I find this deeply problematic as it reinforces an unhealthy, hierarchical model of work.

I now intend to expand the workshop to include a section on collaboration, prompting students to reflect on how they work with others and the importance of valuing all contributions. Respect for the full team from technicians to designers is key to building inclusive, ethical theatre practices.

This process has made me reflect on how much of my own creative practice has been shaped by exclusion language barriers, unfamiliar systems, or just not feeling like I belonged in certain spaces. It’s made me more aware of the privilege I now hold in my role and the responsibility that comes with it. The workshop reminded me that teaching and learning can happen in many forms and that technical spaces can be powerful sites for critical reflection and transformation.

I’ve learned that creating inclusive spaces doesn’t mean having all the answers it means being willing to ask difficult questions and to sit with uncertainty. It also means believing in the creative potential of students to think critically, act ethically, and care deeply about the work they make and the people they make it for

Holding the workshop reminded me of the need for care-based pedagogy. Discussions were emotional and complex, and while I held space with empathy, I recognised the need for better support structures. One challenge was the emotional labour involved for both students and myself. In future iterations, I plan to build in breaks and possibly offer optional one-to-one follow-up sessions, allowing more time for processing and support.

Next Steps

My goal is to embed this workshop more formally into the curriculum not just within this unit, but across other pathways where it fits naturally into the design process. I also plan to incorporate it into our technical skills passport sessions (see Case Study 2 from my Unit 9), making it accessible to students across all courses.

Additionally, I’d like to run sessions with the technical team so we can reflect on our own practices and discuss how we can support inclusive student work within the scope of our resources. While technicians aren’t typically seen as “teachers,” our role is pedagogical. Students spend extended hours in technical spaces, and those informal settings often create the conditions for meaningful learning and conversation. They are ripe spaces for inclusive, student-led dialogue and development.

This workshop is just the start of a wider effort to embed inclusive practice into the heart of production not as an afterthought or a policy directive, but as a shared, student-led dialogue. My belief is that sustainable change comes from the ground up by empowering students to interrogate and redesign the spaces they work within.

Conclusion

This intervention was never meant to be a standalone solution. Rather, it is a beginning a prototype for how student voice and reflective pedagogy can disrupt normative production practices in theatre. By centering inclusion in both theory and practice, we can begin to build theatre spaces that reflect the richness and complexity of the communities we serve. Inclusion, after all, is not an add-on; it is the foundation of meaningful creative work.

References

Crenshaw, K., 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), pp.139–167.

Cox, L., 2020. A Call for Change: Utilising Discomfort Pedagogy as a Decolonisation Tool in Teaching and Learning Practice. [Lecture] UAL Teaching Platform. [Accessed 8 June 2025].

Haraway, D., 1988. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), pp.575–599.

Jaskolski, K.O.K., 2021. How to be a superhero: stories of creating a culture of inclusion through theatre.

Kuppers, P., 2014. Disability Culture and Community Performance: Find a Strange and Twisted Shape. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Merriam-Webster, 2024. Inclusion. [online] Merriam-Webster. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/inclusion [Accessed 8 June 2025].

Moore, J. (2021). Changing the World One Play at a Time; The Intersectionality of Changing the World One Play at a Time; The Intersectionality of Theatre and Activism Theatre and Activism Changing the World One Play at a Time The Intersectionality of Theatre and Activism. [online] Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1478&context=wwu_honors [Accessed 8 June 2025]

Nijkamp, J. and Cardol, M. (2020). Diversity, opportunities and challenges of inclusive theatre. Journal of Social Inclusion, 11(2), p.20. doi:https://doi.org/10.36251/josi.153.

Oliver, M., 1990. The Politics of Disablement. London: Macmillan.

Oliver, M., 2004. The social model in action: if I had a hammer. In: C. Barnes and G. Mercer, eds. Implementing the Social Model of Disability: Theory and Research